The Power to Read

“Reading into or reading out of: reading scripture should make us uncomfortable and ask us to learn.”

[First given as a sermon on August 24, 2025]

Find this interesting? Please register for the upcoming class inspired by it:

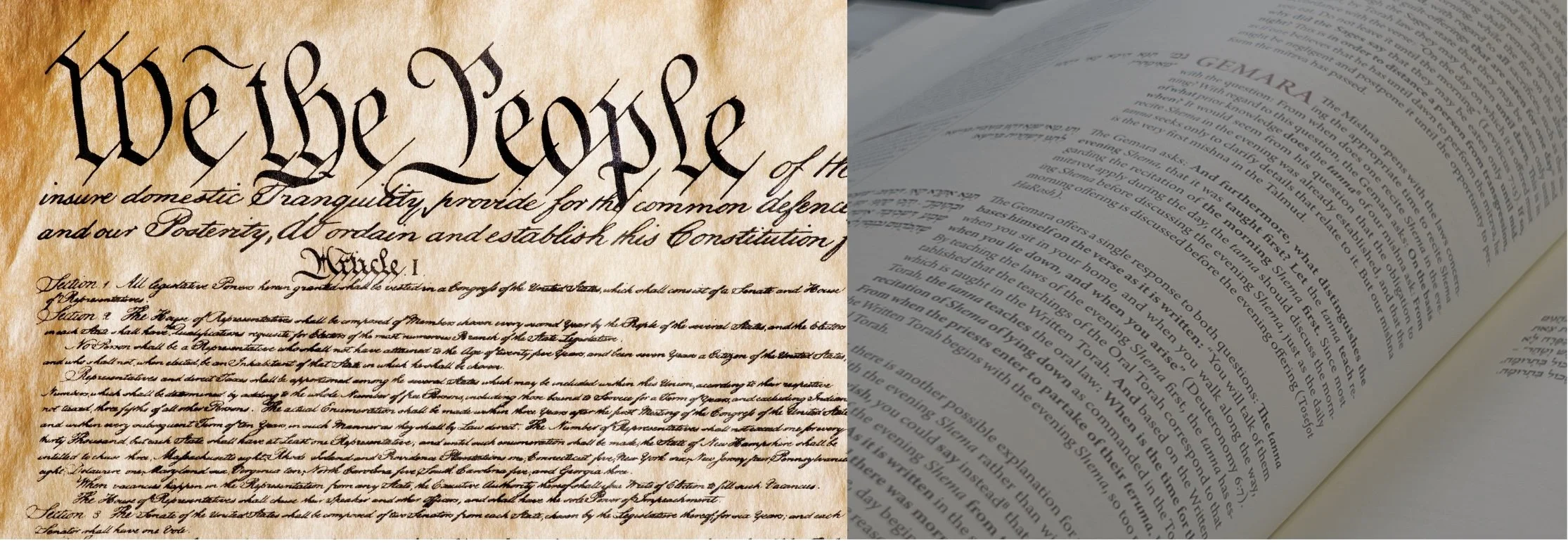

Original and Amendable: Reading the US Constitution in Light of Rabbinic Legal Methodology

Once, when meeting an African American minister for the first time, I was asked, more interrogated: “Do you do exegesis or eisegesis?”

I must admit, no one had used both those words to me since classes in rabbinical school!

After giving the apparently correct answer, namely “exegesis”, the minister told me that he observed serious caution in new relationships with faith leaders and wanted to know if I read scripture in ways that would justify enslaving African Americans. We can use the texts that we hold sacred and important to rationalize abhorrent behavior. This minister, understandably, would refuse partnership with someone who would use texts to justify their own unethical opinions.

In Deuteronomy, Chapter 13, Verse 1, the Divine says: “don’t add or take away from anything I tell you.”

This seems to say we must take the entire teaching literally, word for word.

And yet, none of us do.

Truly – no one adheres to all that is written in Scripture – it is not possible.

Some people try, that’s for sure, but everyone must interpret, and our texts often demand contradictory things from us.

Furthermore, Jews have never taken the entire text literally. Reading farther on in the Deuteronomy, Chapter 13:6, it says: “Now that prophet or that dreamer of dreams is to be put-to-death.”[1] This contrasts with the caution against the death penalty in Jewish traditions. We have a much later text, from the Mishnah, which dates to around 200 CE, over 1,800 years ago, that shows the reluctance with which the death penalty was used for a capital crime. This long discourse shows that ancient Jewish courts made the death penalty so difficult to impose that it almost never happened. The early rabbis supported this with this teaching:

Adam the first person was created alone, to teach you that regarding anyone who destroys one soul, the verse assigns them blame as if they destroyed an entire world, as Adam was one person, from whom the population of an entire world came forth. And anyone who sustains one soul, the verse ascribes them credit as if they sustained an entire world.[2]

Recognizing that it is all well and good for the ancient rabbis to have interpreted away literal readings, while also admitting that Jewish culture reveres the writers of our ancient texts as bearing more authority than we ever can, how can contemporary Jews claim authentic interpretations when the text says: “add and subtract nothing”?

For methods of interpretation, we often divide into two general camps, those of us who try to do exegesis, and those who use eisegesis. Exegesis asks us to learn from the text –reading out of the text. We use the entire canon to help us create context to understand what it says. Eisegesis uses what we think already as a lens on what the text says – reading into the text.

Let’s dismiss most eisegesis from the outset – those who use it often flagrantly bring a text to prove what they already think. They are not endeavoring to learn something from the text. They attempt to teach their own perspectives using the text for their own devices. This seems to be clearly “adding and subtracting” from the text and makes it difficult to adhere to our text today. We will return to all the people who nonetheless do this.

For those of us trying to engage scripture in “good faith” – we need to learn from it, to use it as a source of wisdom not a proof of how we are already wise. In our death penalty example, we see ancient rabbis clearly dismissing an entire form of justice from the Five Books of Moses, the central canonical text for the Jewish people. There are a lot of death penalties enumerated in scripture – for violating the Sabbath (Exodus 31:14), for idolatry (Deuteronomy 17:5), even for being a disobedient child (Deuteronomy 21:18-21), plus the text we read today about the false prophet being put to death. How do the rabbis, who claim absolute devotion to doing what the text says, not only as a religious observance of faith, but also most importantly as a civic law for the basic functioning of their society, allow themselves to so clearly “subtract” from the text while also adhering to it?

The rabbis start with principles that the entirety of the teachings of Judaism lay out clearly. We cannot say that life is important, as shown by the story that tells us that we are all descended from one person and therefore every person contains the potential for an entire world, and be so cavalier about life’s importance that people are put to death all the time. The rabbinic tradition of reading text this way in Jewish society dates back formally at least to the Babylonian Exile, when the earliest academies were founded and Jews needed to figure out how to apply Biblical teachings away from the centers in Jerusalem – that’s more than 2,500 years ago. That means that from the very earliest days of attempting to use Biblical texts as a guide for all of the Jewish people, Jewish scholars developed a system of reading and interpretation that was not based on a slavish literal interpretation – “do this because it says so” – but in fact started with fundamental questions about what the text was trying to teach us as a whole. What are the principles of the society that we hope to build together?

The real principles are often found in the stories, and they help us to understand how to read texts that are often inconsistent. The story shows us the teaching and serves as a more powerful example than any listing of “thou shalt’s” and “thou shalt not’s”.

Jewish exegesis is informed by principles of the text that require us to NOT do literal commands that are contrary to the principles found in the stories that show us what society could be like when we work together. These readings receive support from Jews throughout history in large part on account of the inherently communitarian and democratic approaches of Jewish culture – Jewish authorities really do “serve at the pleasure” of the Jewish people historically.

We see this all the time today because people in power regularly say they “only do what the law says” while reading it entirely differently from its plain language or ignoring plain meanings altogether. Public textual interpretations go directly at the flawed usage of eisegesis that we dismissed and that the African American minister cautioned me about. So many tell us that they can or can’t do things based on their readings of texts. We have leaders claiming that the plain text of the US Constitution doesn’t say what it clearly says, like that every person has certain rights regardless of citizenship. We have religious people saying that their interpretations of scripture must apply to all of us, regarding our own relationships, women’s health, and personal identity.

The Supreme Court used a tortured reading of the Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution to requalify Donald Trump to run for president. Here’s what the text says:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.[3]

The Supreme Court decided that this part of the Constitution was not “self-activating” and used what was clearly tortured reasoning to deny the State of Colorado the power to remove a candidate from the ballot because the State has no jurisdiction over Federal candidates (despite States’ Constitutional responsibilities to run Federal Elections), reading the Congressional power to “remove such a disability” as an additional requirement that Congress must first impose the disability.[4]

Apologies for getting into the weeds of Supreme Court decisions.

Yet, this is the point, and this is the problem with these two terribly “my eyes are glazing over terms” – exegesis and eisegesis – they are stand-ins for the real thing that’s happening, which is about power, the use and abuse of authority, and the denial of rights and power to the people.

When someone uses a text to explain why they get to tell us what to do:

- especially claiming a tortured reading as a plain reading that we must obey, like the Supreme Court’s machinations above, or their use of “originalism” or the phony history that they attempt to do with “history and tradition” arguments, or not even telling us their reasoning at all, as they have repeatedly done on the so-called “Emergency Docket”;

- or a faith leader attempting to end discussion by saying “Scripture says so”;

- or a political leader claiming that they have the power to do something because they looked for and found an obscure legal decree;

what they are really saying is that they have power over us, they have the authority to tell us what language and text mean, that they can make any argument they like to perpetuate their power at the expense of our powerlessness.

In contrast, when we offer a set of principles to read a text with one another, to explain why this way makes sense and that other way makes less sense, we engage in the conversation because we are in community together, because we respect that each of us is a reflection of something sacred, something infinite in the universe, and a fundamental principle behind that is that I don’t get to tell you what to do because I said so. We honor the teaching of the rabbis that we think of ourselves as all descended from one source and that therefore we are all equally endowed with reason, and merit, and value, and wisdom to interpret. We accept that our difference of opinions, often uncomfortable, is the source for productive discussion, out of which will emerge something greater than your opinion or my opinion, namely our shared opinion.

The most important aspect of life together is building community and power collaboratively, through community, so that we can work with one another. This isn’t easy. It takes work, and listening, and admitting that we don’t know everything ourselves, and that solutions are found in compromise and collaboration. When instead we follow a less arduous path and submit to the sovereignty of a one-opinion, one source of wisdom for all of us model, then we give up our rights to self-determination and freedom for all of us together.

Let us learn with one another, develop principles that we can all work on together, and build something better, more inclusive, with liberty and justice for all.

[1] Fox, E. (1997). The Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. Schocken, p. 912

[2] Steinsaltz, A. (2007). Mishnah sanhedrin 4:5. Sefaria: a Living Library of Jewish Texts Online. https://www.sefaria.org/Mishnah_Sanhedrin.4.5?lang=bi&with=all&lang2=en

[3] The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. (1866, June 13). National Constitution Center – The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/amendments/amendment-xiv

[4] DONALD J. TRUMP, PETITIONER v. NORMA ANDERSON, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF COLORADO. (2024, March 4). Supreme Court of the United States. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-719_19m2.pdf)